Seoul: a dive into a world of technology, entertainment, and entrepreneurship

- Date

- Written by Miguel Pereira

Not long ago, we would have headed for Silicon Valley, Israel, or Berlin. But today we turn our gaze to the East. Asia has the creativity, the money, and the technology, but also an army of users willing to experiment and immerse themselves in anything that sounds like innovation. It’s inherent in their culture. And if there’s one place in Asia that’s emerging as a bright spot on the innovation map, it’s South Korea, a country where the lifestyle is steeped in technology, entertainment, and experimentation.

The inspirational trip to Seoul that we organized with our partners at C4E allowed us to validate learning, get inspired, get surprised, validate some premises, and take the pulse of the street. It has been a fascinating trip, intense, perhaps too brief, but certainly timely and refreshing.

The tour had four axes of content: the metaverse and immersive technologies; the world of incubation and entrepreneurship; retail trends; and the culture and lifestyle of Korean society, with special emphasis on the way they understand entertainment.

Personally, the experience I found most surprising was T.um’s future experience, a trip to Hi Land, an imaginary smart city in the year 2053 (30 years from now), connected to the data network of SK Telecom, the leading mobile company in Korea (and facilitator of the experience). It is a futuristic and hyper-technified vision in a devastated planet, of total connection between the city and the people; an immersive, visual, sensory, and interactive experience… All senses are stimulating in an adventure that combines AI, metaverse, mobility and climate change. A true spectacle that forces you to reflect on what the future of society may be like in just 30 years.

You leave the place with your heart racing and a certain restlessness in your soul. But whether you like what the future looks like or not, the experience is impactful and memorable. After the immersive experience of Orange’s Eternelle Notre-Dame in Paris reconstructing the history of Notre-Dame Cathedral since the 12th century, T.um is the most impressive thing I’ve ever seen in virtual reality. And it is interesting how virtual reality allows us to reconstruct the past or project the future with the same efficiency. Always the technology at the service of the narrative; never the other way around.

And speaking of immersive technologies, I was also struck by DoubleMe, a fascinating startup developing the metaverse beyond screens, playing with augmented reality and mixed reality applied to real world spaces; a service they call “real world metaverse as a service”. According to their vision, thanks to the real world metaverse, endless virtual possibilities can be used in any physical place, simply by adding layers of extended reality, usually augmented reality or mixed reality.

At DoubleMe they also have a delightful space called The Cave –it’s in the basement of their offices–, which is half technological showcase, half art showroom, where you can enjoy their virtual proposal mixed on real physical spaces. It is also in development in other places around the world. Hypnotic.

The visit to DoubleMe taught me a few things. First, the commitment to extended realities; the determination to use immersive technologies, not just to build virtual worlds, but to create virtual layers over real physical spaces. This philosophy opens a huge potential for applications in all kinds of industries, because you can do almost anything, in any space, without limitations, from creating a zoo inside a store, to traveling to the moon or going inside the human body.

Also, as a curiosity, they use a technology to create holographic avatars in real time with cameras that scan your body in a matter of seconds. These avatars can be used immediately in virtual meetings, in the style of Meta’s Workrooms, but they do it, again, with the vocation of making the experience happen in a real space.

Incidentally, the glasses we tested at The Cave were a Chinese-made replica of Microsoft’s HoloLens, but at a cost of “only” about a thousand dollars, and we’re told that cost will soon drop to a level above $300 –Microsoft’s HoloLens currently cost about $3,500.

To put the importance of this startup in context, DoubleMe’s clients include Telefónica, and Samsung has just become a shareholder.

In the world of entrepreneurship, we visited incubators such as the Korea Startup Forum, an organization created by Korean companies to promote entrepreneurship and obtain favorable conditions from the government for the creation of new companies. They seek, among other things, to develop what they call a “startup friendly legal framework”. Founded in 2006, it has around 2,000 startup members. They add around 200 new ones every year, and here is an impressive fact: of the 22 Korean unicorns that exist today, 13 have been developed within this organization.

We also visited the AI Hub in Seoul, officially called “AI Yangjae Hub”. It is Korea’s first AI technology startup development institution. Opened in 2017 it is a mix of incubator and accelerator, publicly funded, currently housing about 100 startups related to the world of artificial intelligence. Apart from the “resident” companies it also has partner companies and aims to create a real entrepreneurship ecosystem around AI.

And finally, we also visited D-Camp, one of the most veteran startup accelerators in Korea. The center we visited is Front 1, with more than 120 startups installed, one of many they have throughout the country. D-Camp was born out of a Korean government initiative that forced funding from the entire banking sector in Korea. Of the 19 investing banks, all but one –Citibank, which is American– are Korean.

As lessons learned in the world of entrepreneurship in Korea, I take away the following reflections:

- High regulation. Despite having a Ministry of Startups, Korea is a country with a tremendously restrictive legal system in matters as important as getting a work visa for a foreigner or receiving government approval to launch a new product. According to entrepreneurs, the government has a certain fear of technology -specifically, technology platforms- and protects itself with legislation.

- Focus on light innovation. It has been a constant in the visits: innovation in Korea is more oriented to developments and applications of existing technologies than to truly disruptive innovations. Even so, the level of innovation in the use of technology is overwhelming.

- Difficulty in globalization. This is a country with enough size to generate internal turnover (50 million inhabitants), and at the same time, with difficulties to connect with the outside world: they are de facto an island (if we do not count the border with North Korea), few people speak English, the language is difficult, and the geopolitical context forces them to protect themselves from the outside world, etc.

- Money is not a problem; talent is. For this reason, part of the work of incubators and accelerators is aimed at nurturing talent, attracting young entrepreneurs, and even re-engaging senior professionals. Along the same lines, they seek to create connections, to generate a virtuous circle of collaboration and learning. They talk a lot about the importance of developing a “startup community”.

- There is a whole generation that sees entrepreneurship as a professional career, linking one project to another, supported by public and private fundings. This certainly produces a certain inflation of projects, but also, by sheer statistical force, generates a torrent of companies with disruptive offerings that end up being successful.

- A firm commitment to the development of artificial intelligence and extended realities as a strategy for the country and for entrepreneurship ecosystems.

Another of the most fascinating areas of the visit was the world of retail. On this trip we visited the huge Hyundai Department Store, in Yeouido, and Starfield COEX Mall, in the Gangnam neighborhood, birthplace of the famous Gangnam Style by Korean pop star Psy. I was struck by the sophistication of the offerings, both in the level of the products and in the approach to the consumer shopping experience, with extreme attention to detail and a subtle but effective use of technology.

On an individual basis I was struck by the Uncommon Store, with no employees, fully managed by technology, very much in the style of Amazon Go in the US. Shoppers register with an app on their mobile, enter the store, take the products they want, and when they leave, they are automatically charged with the payment method indicated in the app. The store is monitored by a myriad of cameras that monitor every movement of users inside.

And I was also impressed by the Starfield Library, which is probably the most impressive library in the world, with shelves dozens of meters high, and a striking interior design, as if it were an open shopping mall, without walls. It is interesting to see such an analog and physically striking place in the midst of such a technological world.

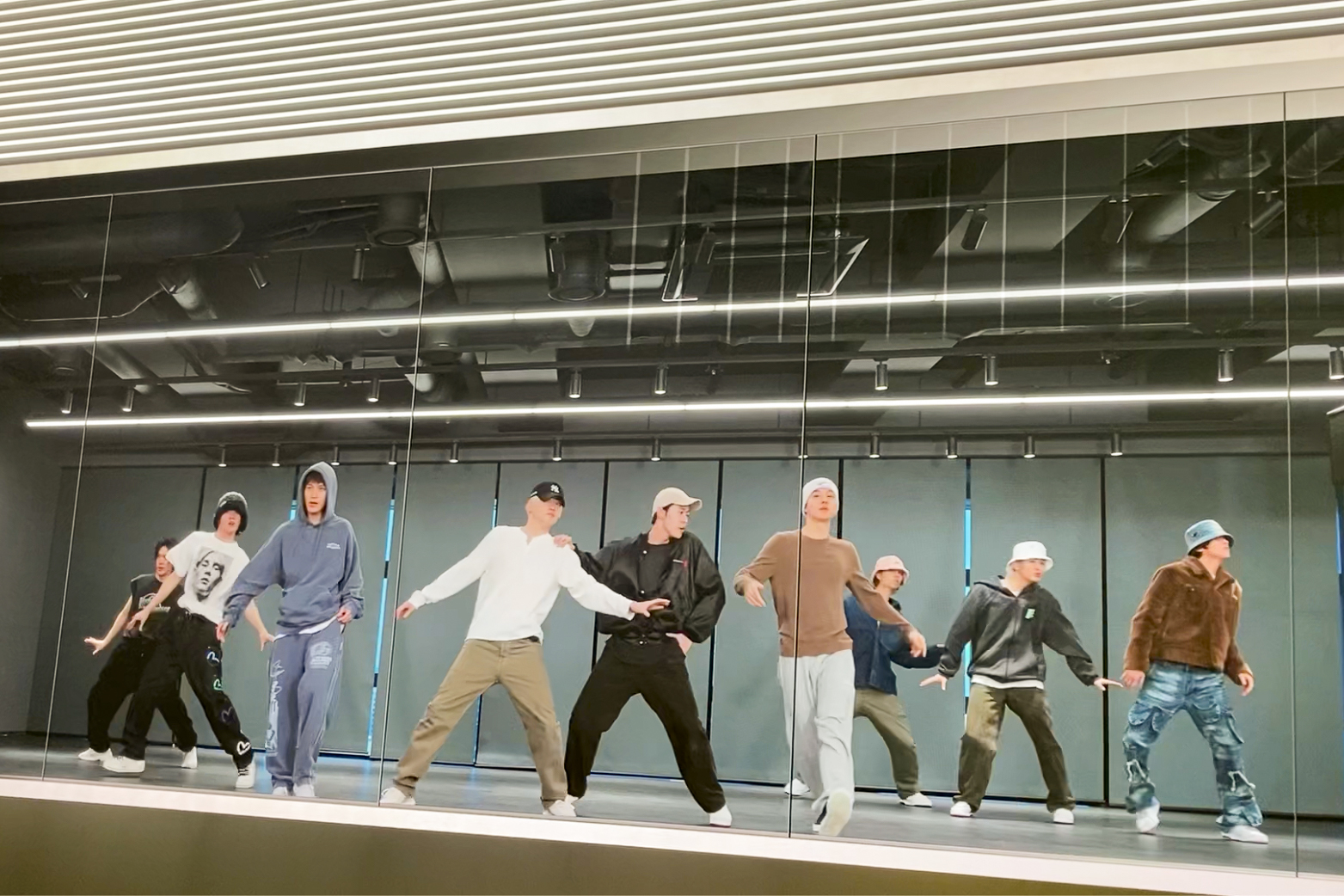

In the world of entertainment, we experienced pop concerts in the street amidst the madness of fans (the first concert with artists performing through holograms took place in Seoul), themed stores for fans of teenage bands, and amazing shows, among which Nanta, a cocktail of comedy, Korean cuisine, acrobatics and rhythm, a lot of rhythm, took the cake. A very Korean humor that demonstrates the important role of gastronomy in Korean culture.

In addition, in the streets of Seoul I was struck by the gastronomy, delicious, exotic, and omnipresent; the impressive education of Koreans (to mention an anecdote, there are almost no litter garbage cans in the streets, and despite this it is impossible to find a piece of paper on the ground), and, above all, the overwhelming presence of screens. They are just everywhere; wherever you look, indoors or outdoors, there are displays of all sizes –but always of great quality– broadcasting messages and content non-stop. There are screens that are entire facades of buildings, endless linear storefronts, cubes and tetrahedrons with screens on all their faces, digital panels on every corner… And of course, everyone walks around the subway and the streets immersed in their personal screens; the latest generation of cell phones.

And then there is the language barrier. Korean is an unreadable language for us and almost inaccessible (it has twenty-something vowels), and very few people speak English. Considering the communication difficulties and the cultural differences, this article could perfectly be titled ‘Lost in Translation… in Seoul’.